Salmonberry I am pacing around the house because someone is knocking at my door, but I can't seem to find my pants. When I peek through the blinds, I can see her wearing a bright pink hat and a frilly dress of green lace. I can't I won't I mustn't go out there. I wait until the golden hour turns to a dark red blush. Then I open the door and in rushes the warm breeze of summer. --Ansley Roberts

Three shrubs leaf out and flower first in spring.

In Celtic traditions, Imbolc signifies the turn of winter to spring. This seasonal festival is usually held on February 1. Some folks refer to Imbolc as a midwinter festival because February 1 is far from the vernal equinox we recently experienced on March 21. As the spring equinox is the time of year with days to nights. This date is the more modern seasonal shift to spring. However, the climate and latitude of the British Isles, where Imbolc was traditionally celebrated, are quite similar to where we live in the Pacific Northwest. Which points me to considering a few other factors besides the daylight hours as indicators for springtime.

The British Isles (England, Scotland, and Ireland) and most of Europe rest between 40-60 degrees latitude, which is roughly the same latitude as the Pacific Northwestern states in the United States and up the Western coast of Canada. Both the Pacific Northwest and the British Isles have a relatively similar climate with four somewhat mild seasons and cloudy, drizzly weather. With all of this in mind, our spring in the Pacific Northwest starts earlier than March 21.

How do I know this? Because of my dear friend, Osoberry. If you walk through the forest in early February, you’ll find one species of shrub budding out with bright green leaves. This is the osoberry! This is the first sign of spring in the Pacific Northwest. After osoberry buds and begins to form flower clusters, salmonberry and red elderberry aren’t far behind.

These early blooming native shrubs might be a little difficult to tell apart at first, so I decided to create a little comparison guide for distinguishing the differences between salmonberry, red elderberry, and osoberry.

This week’s publication is free for your viewing pleasure!

However, only paid subscribers have the joy of reading my entire in-depth plant profiles. Each week, I introduce an ethnobotanically significant plant ally that is in season. If that sounds like the kind of content you want in your inbox every week, please subscribe!

As always, I appreciate your support no matter if you’re a paying member or not <3

Comparing Salmonberry, Red Elderberry, and Osoberry

Obviously, these shrubs look VERY different as they start to flower and fruit. But! I noticed that the leaves might look rather similar before they start showing. Knowing how to tell which one is elderberry or not is most important because all aerial parts of the elder are toxic except the flowers.

This is how you can tell salmonberries, osoberries, and red elderberries apart:

Salmonberry

These yellow to orange berry-producing shrubs are in the same family as plums, roses, and many other fruit trees. It’s genus is Rubus just like blackberries and raspberries. The specific epithet is spectabilis, which I rather love because the flower really is a spectacularly hot pink (hence the name). Latin, once again, isn’t that creative.

Anyways, the easiest way to tell these shrubs apart from the oso- and elder- berries is the bark, leaves, and flowers. The leaves come in sets of three leaflets. Once the leaves are fully developed, the two bottom leaflets resemble the shape of a butterfly! Salmonberry stems are a tan-brown with rather benign thorns (compared to Himalayan blackberries) and an upright stature. The flowers, as you can see below, are simple, five petaled pink beauties.

The flowers of the salmonberry are edible and pretty tasty. I usually like to use them as decorations on cakes or sprinkled into my wild greens salad. The berries are remarkably NOT as spectacular as the name would suggest … however, they are the first berry to fruit in the Pacific Northwest so I’ll not be picky.

These berries are rather distinct with their bright orange color. They ripen into a red, and sometimes so much so that they develop into a dark purple. Not all salmonberries fully turn red or purple, so I generally eat them regardless of their color. The flavor is rather bland, but sweet. I like them in jams and jellies or as cake decorations myself.

Red Elderberry

She’s a knobbled old hag and I love her. At first glance, this is certainly the shrub you might mistake for an osoberry; but it’s a mistake you really mustn’t make. Unlike salmonberry or osoberry, the leaves and stems of elderberries contain toxins that aren’t safe to consume. Three distinguishing factors for elderberries is their warty-looking bark, opposite branching, and pinnately compound leaves (see images below for reference).

Red elderberry (Sambucus racemosa) is one of three native elderberry species in the United States. The other two species, black and blue elders, are native to the east side of the Cascades and are generally only found in landscaping on the Western side. Unlike the black and blue species (which also need processing to remove the seeds), red elderberries are not typically considered safe for consumption due to them having higher levels of toxins than the other two.

I’ve been waiting for the elders to bloom to write my elderberry profile. It’s hard to keep up with all the plants blooming and fruiting in the spring! There’s just so much I could cover. Once the elders flower, there’s really not much else in the spring to mistake them for. Maaaaaaaaybe you could make the mistake of comparing them to a ninebark or oceanspray, but the bark, opposite branching, and red berry clusters are a dead giveaway.

If you’re having trouble distinguishing elderberries from other trees and shrubs in the Pacific Northwest (specifically in winter), I would encourage you to look closely at the branching pattern for clues as to which plant you’re looking at.

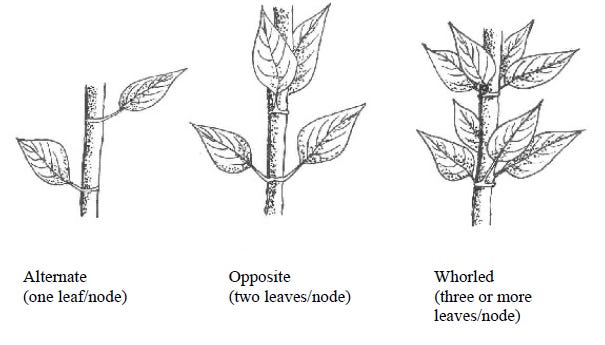

Just like the big leaf maple, elderberries have opposite branching (see middle photo above), which means that they produce nodes directly across from each other compared to alternate or whorled patterns.

Osoberry

I wrote an entire profile on osoberry back in February as my first plant profile in A Forager’s Diary. It’s a little less in-depth than my recent publications, so thanks for being with me as I refine my work.

Osoberry (Oemleria cerasiformus) is one-of-a-kind. No really! There actually aren’t any other species in the Oemleria genus. It has simple leaves with smooth margins. This is an important identifying feature since they sometimes look similar to cascara later in the season. The leaves taste like cucumber and are delicious when added to your water bottle on a hike.

Just don’t FORGET them in your water bottle for a week and then take a sip of your water on a bike ride and choke on rancid osoberry tea. (Ask me how I know …)

The osoberries themselves have a bitter cucumber skin flavor, but they’re not bad. These berries resemble tiny purple plums, hence their Western common name, which I do not prefer, “Indian plum.” There’s a nice-sized pit in the middle, too, so be sure not to crunch them down if you haven’t had one before.

Not particularly useful in jams or anything because of their bitter flavor. I generally have a taste while I’m on the trail, then leave the rest for the birds.

That’s about all I have to say about that. I hope this short reference guide helps you find some delicious berries this spring and get to know the local flora better!

If you’re into watching short videos on Instagram or YouTube, I also release video content on those platforms about plants, wilderness survival, and rewilding.

Know someone who would love to get weekly foraging content in their inbox?